The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ annual campaign runs only throughout March, but we appreciate the fact that nutrition education is important all year round. In our first article, we followed the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) “MyPlate” guidelines and split our plate into four food groups: Proteins, vegetables, fruits and grains. We also addressed these food groups one-by-one, first covering proteins, their nutrients and health benefits, and the types that are best for us. (Read Part 1 here.)

In our second feature, we tackled fruits and vegetables. After pointing out their numerous benefits and nutrients, we identified the varieties of produce we recommend most by their color. (Read Part 2 here.)

Today, we’re wrapping up our nutrition education series with the food group that, despite its popularity, tends to be grounded in controversy: Grains.

WHAT ARE GRAINS?

Grains are small, dry and hard edible seeds from the Poaceae grass family of flowering plants, called cereals. There are numerous varieties of cereal grains, including rye, barley, millet and sorghum, as well as the most heavily cultivated and consumed cereal crops including maize (corn), wheat, oats and rice. Grains are considered worldwide food staples, meaning they’re a constant component in populations’ daily diets.

According to Statista, over 42 percent of grain in the US acts as animal feed, while 36 percent is used to produce ethanol and 21 percent is actually consumed by people. Interestingly, another study shows that the daily per capita intake of grains in Americans had climbed dramatically over a 40-year period, from 415 calories in 1970 to 585 calories in 2010. Using that statistic on men following a 2,000- to 2,500-calorie diet, grains account for 29 or 23 percent of their daily intake, respectively.

Grains are a major source of carbohydrates, which – along with fellow macronutrients proteins and fats – provide energy. In fact, carbs are the primary energy source for your brain[1] and your muscles.[2] Yet, their reported properties have also become a source of controversy.

DON’T GO AGAINST THE GRAINS

A glut of low-carb, gluten-free diets in recent years has convinced many to believe that grains are bad news and should be expelled from your diet. Some of the more prevalent beliefs about grains include a) they can adversely raise your blood glucose and insulin levels, b) they can be a source of antinutrients, compounds that can block your body’s absorption of nutrients and promote inflammation, and c) their carbs are calorie-dense and fattening.

Ultimately, we leave it to you to decide whether or not you want grains in your everyday diet. Yet, we’d be remiss if we didn’t point out that many of the negatives surrounding grains can, and should, be taken with…well, a grain of salt.

Grains are actually divided into two subgroups: Whole grains and refined grains. And the healthier choice of the two, by far, is whole grains. They’re B vitamin-rich, fiber-heavy and nutrient-fueled, including magnesium, iron, selenium, zinc, manganese and phosphorus. the USDA recommends that whole grains constitute at least one-half of your total grain intake (which, for adult males, ranges between 6 and 8 ounces).

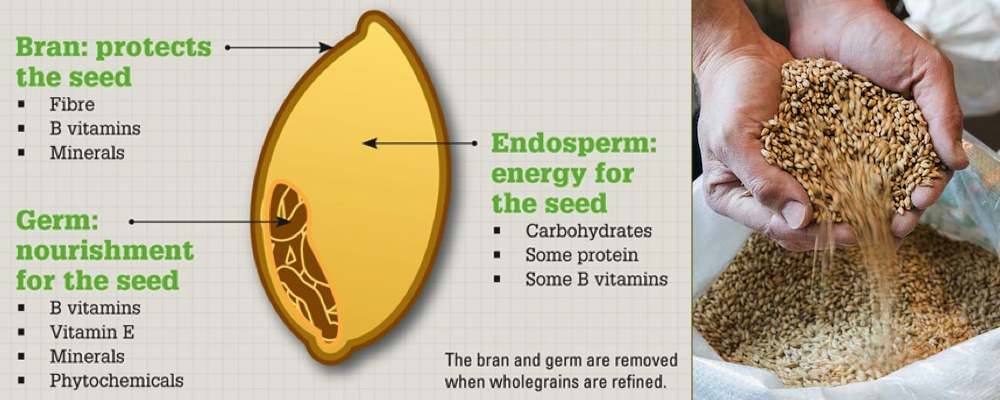

The nutritional value from both subgroups comes down to grains’ anatomy. Whole grains contain the entire grain seed, or grain kernel, which is composed of the bran, the endosperm and the germ. A fiber-filled outer layer, the bran shields the seed and contains B vitamins and trace minerals. The endosperm is the starchy middle layer that supplies the seed with carbohydrates, some B vitamins and protein to create energy. At the core is the germ, which nourishes the seed and is rich with antioxidants, Vitamin E and B vitamins, unsaturated fats and phytochemicals.

The health benefits of whole grains are well documented. A 2016 study published in the BMJ[3] cites that whole grains are associated with a lower risk of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and cancer, and premature death. According to a 2020 report in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics,[4] more than 20 randomized controlled trials showed that substituting refined grains with whole grains can improve cholesterol levels, blood sugar control and inflammation.[5]

And what of the controversy surrounding antinutrients? It’s true that compounds like gluten, tannins, lectins, phytates, oxalates and protease inhibitors protect living plants from bacterial disease. However, there’s some debate that these compounds can also greatly reduce plant foods’ nutritional value, or prevent your body’s absorption of those nutrients.

Not all scientists and medical professionals are quite ready to swallow such statements, as there isn’t enough empirical evidence to support them. Concrete research does point out, though, that antinutrients like phytates[6] and tannins[7] are more beneficial to your health, because their antioxidant properties prohibit free radicals from causing cell damage in your body.

That stated, if you’re concerned that antinutrients in your grains may be more harmful than helpful, there’s an easy way to resolve the problem: You can soak the grains in water overnight, or you can cook them in high heat. (Boiling is your most effective option.) There’s also sprouting and fermentation, but it’s faster and easier to go with one of the first two options.

As for those claims that grains and their carbs result in putting on extra poundage, the same can be stated if you eat too much of any food. Whole grains don’t fatten you up. In fact, a 2007 study in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition revealed that a higher consumption of whole grains in test subjects correlated with a lower body mass index (BMI) and a reduced risk of obesity.[8]

There’s more to holding the carbohydrates in grains accountable for your expanding waist size. You’re better off saving the blame game for the sugar and calories that are more often associated with “indulgent” refined grain sources like pizza, cookies, donuts and other sweet treats, or “staple” refined grains found in white bread and flour, pasta and white rice.

"REFINED"? MORE LIKE "REMOVED"

When you read or hear the word “refined,” you may think “improved,” “perfected” or “enhanced.” That’s the intent of refined grains. However, what makes a grain refined is that it has been processed or milled, meaning the bran and germ have been removed. Only the carb-heavy endosperm remains. That, and a whole bunch of now-empty calories. Doesn’t seem too much like “improved,” does it now?

Milling the grain does provide some benefits – the grain is more convenient to prepare and easier to digest, and it has a finer texture and longer shelf life. Yet, such refinement is not without consequence; processing also eliminates half to two-thirds of a grain’s most nutritious elements, including its B vitamins, selenium, Vitamin E, iron and dietary fiber.

To address the loss of nutrients, many refined grains are “enriched,” meaning iron, thiamin, riboflavin, folic acid and niacin are added back after processing. Fiber isn’t, however, and no fiber in your grains is no bueno.

The National Academy of Medicine[9] (formerly known as the Institute of Medicine) recommends that the daily intake of total fiber should range around 38 grams for adult men under age 50, and 30 grams for males 50 and older. Unfortunately, Americans already average way less than that – between 10 and 15 grams every day. So, if you’re also eating grains or other foods that are low in fiber, you may increase your chances of constipation, weight gain and heart disease, and reduce your protection against colorectal cancer.[10]

We don’t mean to be rough on refined grains – they can be quick to make, tasty and very difficult to resist. Sitting in a restaurant and not touching that basket of bread at the start of a meal may at times seem impossible. Ultimately, though, the satisfaction these grains provide is as temporary as that full feeling in your stomach. Refined foods are so easy to digest that your blood sugar levels spike up fast, then crash down just as quickly, leaving your body to think it’s hungry again.[11] Before you know it, that rollercoaster-like rush of fullness and energy you felt is over, and you find yourself back in line craving another turn – or in this case, reaching for another piece of bread.

WHOLE GRAINS WE RECOMMEND

Okay, we’ve established whole grains as our go-to source of grains. Which among them are the healthiest?

In truth, you can’t really go wrong with any whole grain; their minerals and vitamins make them nutrient powerhouses. Therefore, we’ll pick our “Succulent Six” and point out some of the health benefits that each provides.

• Oats: Ranking high on the list of popular whole grains, oats are a gluten-free option filled with antioxidants and nutrients, including a super-soluble dietary fiber called beta-glucan. This particular fiber is known for delivering where it matters most, and can reduce your LDL and total cholesterol levels.[12]

• Teff: Another gluten-free cereal grain, teff (or tef) is an ancient crop that contains the highest iron and calcium[13] among other cereals, meaning it’s great for boosting your circulation[14] and promoting bone development and protection,[15] respectively. It’s also a terrific source for all amino acids, most notably lysine, which can reduce both hypertensive individuals’ blood pressure[16] and your levels of the stress hormone, cortisol.[17]

• Barley: This grain is at its wholesome best when it’s hulled, meaning only its tough, inedible outer husk is removed. (Pearl barley is more common and quicker to cook with, but its bran layer has also been removed, making it less nutritious and no longer a whole grain.) A half-cup of the hulled grain contains almost your entire recommended daily allowance (RDA) of the trace mineral manganese[18] and nearly half your daily allowance of Vitamin B1 (thiamine),[19] both of which are significant contributors in effectively regulating your glucose metabolism.

• Freekeh: The name might make one think of Rick James’ seminal 1981 “super” hit and, truth be told, this ancient whole grain gives us much cause for dancing. Native to the eastern Mediterranean and parts of North Africa, freekeh is roasted durum wheat that’s harvested while the grain is young and green. While free of saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium, the grain is stacked with high quality protein, fiber calcium, magnesium and B vitamins. It’s also loaded with the trace mineral zinc, which studies have established helps enable men to produce testosterone[20] and is essential for male fertility.[21] Further research indicates that zinc can also be beneficial for men experiencing erectile dysfunction.[22]

• Corn: Wait, isn’t this a vegetable? Well, corn (or maize) fits the definition of one. However, corn kernels – you know, the stuff that popcorn is made from – in their full form contain the germ, bran and endosperm. Couple that with the fact that it’s the most cultivated and consumed food staple on Earth, and you’re looking at whole grain royalty here. You can also see that in addition to being dense with essential minerals as well as B vitamins and Vitamin C, corn is rich with lutein and zeaxanthin, carotenoids that studies have visibly shown can help prevent age-related macular degeneration.[23]

• Rice: All rice starts out as a whole grain, but you’ll want to stick with the varieties that aren’t refined, like white rice. Therefore, we recommend you go with wild or brown rice, based on your personal preference and health goals. Cooked wild rice (which okay, technically, it’s actually a marsh grass rather than a grain) has the edge in that it has 30 percent fewer calories and 40 percent more protein than its brown-colored peer, and it’s the clear winner when it comes to disease-curtailing antioxidants. (It contains more than 30 times greater activity[24] than white rice.) However, if you’re more into improving bone development[25] and metabolic function, you’ll want to go with the brown rice, which offers six times the manganese as wild rice.

Though we’ve selected only six, there are a plethora of whole grains for you to choose from, including wheat, rye, millet, farro, sorghum, bulgur (or cracked wheat). There are also “pseudo cereals” – plants which produce seeds or fruits that are consumed as grains – like amaranth, wattleseed, buckwheat and everybody’s favorite superfood, quinoa. Each of these grains is distinct with their own set and varying degrees of nutrients, vitamins and minerals. All, however, are healthy options that deserve a spot on your plate. (Just not all of them in one sitting, okay?)

For more "Foods for thought", check out: Part 1: Proteins | Part 2: Fruits and Vegetables

FOLLOW US ON FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM, TWITTER AND YOUTUBE

References:

[1]Slavin J, Carlson J. Carbohydrates. Adv Nutr. 2014 Nov 14;5(6):760-1. doi: 10.3945/an.114.006163. PMID: 25398736; PMCID: PMC4224210.

[2]Elia M, Folmer P, Schlatmann A, Goren A, Austin S. Carbohydrate, fat, and protein metabolism in muscle and in the whole body after mixed meal ingestion. Metabolism. 1988 Jun;37(6):542-51. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90169-2. PMID: 3374320.

[3]Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, Fadnes LT, Boffetta P, Greenwood DC, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ, Riboli E, Norat T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2016 Jun 14;353:i2716. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2716. PMID: 27301975; PMCID: PMC4908315.

[4]Marshall S, Petocz P, Duve E, Abbott K, Cassettari T, Blumfield M, Fayet-Moore F. The Effect of Replacing Refined Grains with Whole Grains on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials with GRADE Clinical Recommendation. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020 Nov;120(11):1859-1883.e31. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.06.021. Epub 2020 Sep 12. PMID: 32933853.

[5]Vitaglione P, Mennella I, Ferracane R, Rivellese AA, Giacco R, Ercolini D, Gibbons SM, La Storia A, Gilbert JA, Jonnalagadda S, Thielecke F, Gallo MA, Scalfi L, Fogliano V. Whole-grain wheat consumption reduces inflammation in a randomized controlled trial on overweight and obese subjects with unhealthy dietary and lifestyle behaviors: role of polyphenols bound to cereal dietary fiber. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Feb;101(2):251-61. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.088120. Epub 2014 Dec 3. PMID: 25646321.

[6]Zhou JR, Erdman JW Jr. Phytic acid in health and disease. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1995 Nov;35(6):495-508. doi: 10.1080/10408399509527712. PMID: 8777015.

[7]Chung KT, Wong TY, Wei CI, Huang YW, Lin Y. Tannins and human health: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1998 Aug;38(6):421-64. doi: 10.1080/10408699891274273. PMID: 9759559.

[8]van de Vijver LP, van den Bosch LM, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA. Whole-grain consumption, dietary fibre intake and body mass index in the Netherlands cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;63(1):31-8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602895. Epub 2007 Sep 26. PMID: 17895913.

[9]Quagliani D, Felt-Gunderson P. Closing America's Fiber Intake Gap: Communication Strategies From a Food and Fiber Summit. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016 Jul 7;11(1):80-85. doi: 10.1177/1559827615588079. PMID: 30202317; PMCID: PMC6124841.

[10]Kunzmann AT, Coleman HG, Huang WY, Kitahara CM, Cantwell MM, Berndt SI. Dietary fiber intake and risk of colorectal cancer and incident and recurrent adenoma in the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 Oct;102(4):881-90. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.113282. Epub 2015 Aug 12. PMID: 26269366; PMCID: PMC4588743.

[11]Lennerz BS, Alsop DC, Holsen LM, Stern E, Rojas R, Ebbeling CB, Goldstein JM, Ludwig DS. Effects of dietary glycemic index on brain regions related to reward and craving in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013 Sep;98(3):641-7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.064113. Epub 2013 Jun 26. PMID: 23803881; PMCID: PMC3743729.

[12]Whitehead A, Beck EJ, Tosh S, Wolever TM. Cholesterol-lowering effects of oat β-glucan: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Dec;100(6):1413-21. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.086108. Epub 2014 Oct 15. PMID: 25411276; PMCID: PMC5394769.

[13]Shumoy H, Raes K. Tef: The Rising Ancient Cereal: What do we know about its Nutritional and Health Benefits? Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2017 Dec;72(4):335-344. doi: 10.1007/s11130-017-0641-2. PMID: 29098639.

[14]Alaunyte, I., Stojceska, V., Derbyshire, E., Plunkett, A., & Ainsworth, P. (2010). Iron-rich Teff-grain bread: An opportunity to improve individual's iron status. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 69(OCE1), E105. doi:10.1017/S002966510999293X

[15]Gebremariam MM, Zarnkow M, Becker T. Teff (Eragrostis tef) as a raw material for malting, brewing and manufacturing of gluten-free foods and beverages: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2014 Nov;51(11):2881-95. doi: 10.1007/s13197-012-0745-5. Epub 2012 Jun 2. PMID: 26396284; PMCID: PMC4571201.

[16]Vuvor F, Mohammed H, Ndanu T, Harrison O. Effect of lysine supplementation on hypertensive men and women in selected peri-urban community in Ghana. BMC Nutr. 2017 Jul 27;3:67. doi: 10.1186/s40795-017-0187-6. PMID: 32153847; PMCID: PMC7050943.

[17]Smriga M, Ando T, Akutsu M, Furukawa Y, Miwa K, Morinaga Y. Oral treatment with L-lysine and L-arginine reduces anxiety and basal cortisol levels in healthy humans. Biomed Res. 2007 Apr;28(2):85-90. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.28.85. PMID: 17510493.

[18]Li L, Yang X. The Essential Element Manganese, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolic Diseases: Links and Interactions. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018 Apr 5;2018:7580707. doi: 10.1155/2018/7580707. PMID: 29849912; PMCID: PMC5907490.

[19]Lonsdale D. A review of the biochemistry, metabolism and clinical benefits of thiamin(e) and its derivatives. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006 Mar;3(1):49-59. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nek009. PMID: 16550223; PMCID: PMC1375232.

[20]Prasad AS, Mantzoros CS, Beck FW, Hess JW, Brewer GJ. Zinc status and serum testosterone levels of healthy adults. Nutrition. 1996 May;12(5):344-8. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(96)80058-x. PMID: 8875519.

[21]Fallah A, Mohammad-Hasani A, Colagar AH. Zinc is an Essential Element for Male Fertility: A Review of Zn Roles in Men's Health, Germination, Sperm Quality, and Fertilization. J Reprod Infertil. 2018 Apr-Jun;19(2):69-81. PMID: 30009140; PMCID: PMC6010824.

[22]Dissanayake D, Wijesinghe PS, Ratnasooriya WD, Wimalasena S. Effects of zinc supplementation on sexual behavior of male rats. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2009 Jul;2(2):57-61. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.57223. PMID: 19881149; PMCID: PMC2800928.

[23]Sommerburg O, Keunen JE, Bird AC, van Kuijk FJ. Fruits and vegetables that are sources for lutein and zeaxanthin: the macular pigment in human eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998 Aug;82(8):907-10. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.8.907. PMID: 9828775; PMCID: PMC1722697.

[24]Qiu Y, Liu Q, Beta T. Antioxidant activity of commercial wild rice and identification of flavonoid compounds in active fractions. J Agric Food Chem. 2009 Aug 26;57(16):7543-51. doi: 10.1021/jf901074b. PMID: 19630388.

[25]Kang M, Song JH, Park SH, Lee JH, Park HW, Kim TW. Effects of Brown Rice Extract Treated with Lactobacillus sakei Wikim001 on Osteoblast Differentiation and Osteoclast Formation. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2014 Dec;19(4):353-7. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2014.19.4.353. Epub 2014 Dec 31. PMID: 25580402; PMCID: PMC4287330.

Related:

• The hard(?) truth about erectile dysfunction, your sex drive and TRT

• WATCH: How to make sense of your injection dosages

• Peak: Who we are, and why we're serious about your health

• 10 things to know when consulting with your hormone doctor

• Order your at-home hormone testing kit